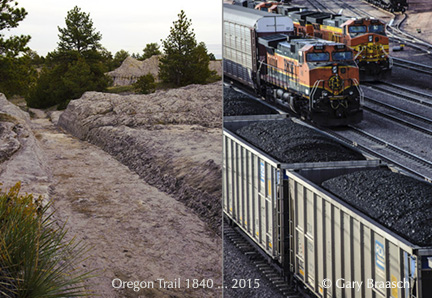

In Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, the old Oregon Trail has become the railroad route for millions of tons of coal.

© 2013 Gary Braasch and Joan Rothlein.

(This photo story was first published by The Daily Climate on December 9, 2013, and picked up also by Grist and Scientific American on Sciam.com. Major points of the text have been updated as of December 2014. Environmental health scientist Dr Joan Rothlein and photojournalist Gary Braasch spent a week in Wyoming to see where so much of America’s coal comes from and the source of proposed coal exports)

GILLETTE, Wyo. – The broad high prairie of eastern Wyoming and Southern Montana was once the bottom of a shallow sea, a rich subtropical swampland for millions of years. Layers of plants began forming peat beds 60 million years ago, later to be buried and compressed into bituminous coal strata.

The Missouri River became the dominant stream as the Northern Rockies formed, with tributaries like the Yellowstone, Powder and Cheyenne rivers running north and east to meet it. Their erosion eventually left coal seams only a few feet beneath the land surface of what today is called the Powder River Basin.

The surface is a rich grassland that was home to herds of bison and native Cheyenne, Crow and Lakota who were forcefully displaced by white pioneers and settlers, who then grazed thousands of head of cattle. Much of this 26,000-square-mile area is still grazed on a combination of private ranches, national grassland administered by the Department of Agriculture, and grazing allotments run by the Bureau of Land Management. BLM also controls the coal, oil and other mineral rights; today that's where the money is.

The region has been a western center of the American coal industry since the 19th century. But only after the Clean Air Act amendments required lower sulfur levels in 1990 did Powder River's low-sulfur bituminous and subbituminous become the dominant U.S. coal for generating electricity, power and heat nationwide. This is one of the largest coal reserves in the world which so far has produced 10 billion tons of the fuel. It also may be the cheapest to mine, with coal sitting near the surface and with a price per ton of $11.50 at the mine, one-quarter the price of coal from other U.S. areas. Thomas Michael Power, a professor emeritus at the University of Montana who studies the economics of energy, told The Daily Climate, "There isn't any other large source of coal in the world that can produce coal that cheaply."

Today the massive deposits, enough to light the United States almost into the 23rd century, have become the center of a regional – and increasingly national – debate: Should this resource continue to be developed, how will it get to market and what is that market? The coal is so cheap that companies began to see profit in shipping it west via vast trains, a mile or more long, then onto giant freighters across the Pacific Ocean to meet China's demand. But once seen as insatiable, that demand fell for the first time at the end of 2014, and China made a pact with the U.S. to begin reducing its greenhouse emissions for which coal is the largest contributor.

Coal is the "dirtiest" fossil fuel, giving off noxious sulfur and mercury fumes and 2.5 tons of carbon dioxide for every ton of ore burned. Natural gas emits about half as much. According to the Energy Information Agency, coal is the source of 44 percent of world-wide energy-related CO2 emissions. These facts and strong community opposition to the idea of rumbling, dusty coal trains passing through towns from Gillette, Wyoming, to Portland and Seattle have made coal exports much less a business certainty.

The drive to develop coal has increasingly pitted ranchers against mining companies in a fight for water resources. Aquifers, pierced by mines, are draining away. What is sweet summer grassland to a rancher is overburden to be scraped away by a mining corporation. Grazing allotments literally disappear as the U.S. Forest Service declares pasture unavailable due to mining activity.

Just south of the Basin in Guernsey, Wyoming, one can see pioneer wagon, oxen and foot-worn ruts from the 1830s Oregon Trail, carved two to six feet deep into sandstone. Now, for miles to the north into Montana the land is rutted, ripped and stripped by 16 huge open pit coal mines, tracked by railroads carrying away the black fuel to power U.S. electrical energy. And increasingly, it's a landscape punctured by gas and oil wells.

A ranch on the Little Powder River north of Gillette, Wyo., now shares the land with the recently built Dry Fork Power Plant. Dry Fork burns coal from a nearby mine to create 385 megawatts of electricity. Only eight years ago coal power created more than half U.S. electricity; now it is down to about 37 percent due to the rise of natural gas and global warming concerns..

Power shovel at work in the Caballo mine, owned by Peabody Energy Corporation, loading coal onto trucks from a 68 foot thick coal seam more than 200 feet below the prairie surface. Under leases from the state and federal governments, area mines are expanding through the grassland soils and surface rock, spitting it out as piled-up spoils and imperfectly restored land.

Forty percent of American coal comes from this part of Wyoming and Southern Montana, centered on Gillette, and almost all of it is burned to generate electricity. Coal burning power plants, according to BLM figures, create 13 percent of total U.S. carbon dioxide emissions – more than any other single activity in the nation. The coal and power industries now face Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) limits on coal plant CO2 emissions under the Clean Air Act.

A Caterpillar truck loaded with coal powers out of the Eagle Butte Mine, which produces about 20 million tons of coal per year for the Alpha Natural Resources company. Not much here is small: The trucks are 40 feet long, 20 feet high at the cab and roll on six 11 foot diameter tires. They carry 200 tons of coal, dumping it onto a conveyor that transfers the coal to trains of up to 150 hopper cars.

Reclaimed mining area north of Wright, Wyo. Coal companies tout the success of reclamation. BLM regulations require performance bonds and say mined areas must be restored to "approximate original contours" with water and habitat in "healthy condition.” But the Western Organization of Resource Councils (WORC) found otherwise in reviewing reports from the BLM Office of Surface Mining: "Coal mining has disturbed more than 162,000 acres of land in Wyoming” WORC wrote,“but only 4 percent of this land has gained final reclamation status” resulting in full restoration and legal release from the bond.

Coal trains approaching and leaving the North Antelope Rochelle Mine, owned by Peabody Energy Corporation. This is the most active coal mine in the United States, producing 111 million tons of coal in 2013 – more than 10 percent of all U.S. production. Dust from blasting, mine work and heavy truck traffic on gravel roads casts a pall over the landscape. EPA monitoring station data shows worsening air pollution since 1980 as more and more coal has been mined.Very few people live directly adjacent to the coal mines now, but mines are expanding near the Gillette and Wright areas. On the range near roads and mines, ranchers report young cattle and horses can suffer from "dust pneumonia" from the pollution.

Rancher L.J. Turner looks after some of his red angus cattle on a pasture he leases from the Agriculture Department's Thunder Basin National Grassland near Wright, Montana. The success of his herd depends on this rich prairie. But underneath lies a thick seam of coal – and the giant North Antelope Rochelle Mine in the background is gobbling up the prairie to get to it. Mining has priority among the values of this federal land, so the mine has been permitted to truck off as "overburden" about 6,000 of the 7,500 acres in Turner's original grazing allotment.

Now there may be harder times ahead. "You just have to take a loss," said Turner from . "That 6,000 acres we lost supported our family."

Turner, born and raised on this land which his family has owned since 1918, points across the 10,000 acre ranch to some of the streams that have dried up in recent years. He blames coal mining. Creeks like Antelope Creek, which rises on part of the ranch, dry up in summer now, except for the spring holes. Fish, beaver, mink and muskrats are mostly gone. "From Antelope Creek north to Gillette all the aquifers are being cut by mines," he said. "Water upstream is draining away."

Turner says the fresh water aquifer lies at about 90-100 feet deep, so when it is sliced open by blasting and power shovels, water collects in bottom of the mines. Some of the water is pumped out, some used for wetting the mine roads or other mine uses. But for a rancher, "it's just gone."

"My biggest concern is water, there’s not enough of it now, and its dirty," said Karen Turner, looking over a map of their ranch and government grassland leases with her husband, L.J. "We drink bottled water because our water smells like hydrogen sulfide, and it didn't used to."

Along with the encroaching coal mines, many wells for oil and natural gas have been drilled recently and more are being negotiated on and near the ranch. The Turner's gain some income from wells situated on the surface of their land, but they do not own the mineral rights beneath. The quiet and traditional ranching life "is gone and not coming back," L.J. Turner said. Ranch hands are hard to find because of the higher-paying oil and coal jobs. Their young adult children love the ranch, but "are not enthusiastic about coming back to do battle," including court fights with state authorities over protection of springs and smaller water sources.

Karen looked up from the map. The drilling and mining, she said, "makes you angry – sick with anger.”

The loading area is a hive of activity at Arch Coal Company's Black Thunder Mine, the second greatest producer but the largest mine in the Powder River Basin. Aerial photos by Skytruth in 2012 showed this mine has dug up and scarred more than 40 square miles – almost the area of the city of San Francisco.

Black Thunder Mine produced 107.7 million tons of coal in 2013 and employed more than 1,600 people. As federal land use laws and regulations are interpreted, nothing seems to stand in the way of the several-hundred-foot deep strip mines in the Basin: Not the tributaries of the Cheyenne and Powder rivers, not their aquifers – which are routinely destroyed or rerouted – and not the National Grassland used by ranchers to feed their herds.

Coal cars stage for loading at the Black Thunder Mine near Wright, Wyo. Up to 100 coal trains are loaded daily in the Powder River Basin and leave day and night on Burlington Northern-Santa Fe's multi-track network, bound for more than 200 power plants to the east, south and increasingly, west.

In the Powder River Basin, coal companies have been paying only a dollar a ton to the BLM for coal from federal land leases, but in summer 2013 one bid of 21 cents a ton was rejected by the BLM and another lease offer got no bids. Analysts peg the slump to two factors: cheap natural gas and climate change regulations. Publically-owned coal is supposed to be sold to the companies at a "fair market price" to meet national energy needs. An Interior Department Inspector General report on Powder River Basin coal in 2013 said that, to the contrary, sale prices have been too low, mine data supplied by the companies has not been independently verified and high export prices for coal not counted in "fair market" calculations. Exported coal fetches up to ten times the approximately $11 a ton price paid by domestic end users. The coal leasing program of the BLM came under additional fire at the end of 2014 when WORC and Friends of the Earth sued the agency for failing to consider the harmful effects of burning coal.

A westbound 115-car BNSF train packed with Powder River Basin coal passing through the Wyodac Power Plant outside of Gillette. Coal companies have been courting both export markets in Asia and port officials in Oregon and Washington, hoping to greatly increase coal exports from the Powder River Basin. Peabody Energy's CEO called it "a new era of U.S. exports … to the world's best market for coal.” Coal export expansion could mean 40 trains a day, rather than the two or three daily now, rumbling the 1,400 miles to the west coast through the environmentally sensitive Columbia River Gorge and passing through scores of towns along the way.

Each hopper car holds about 120 tons of coal, so that a 125-car train carries about 15,000 tons of coal. The trains can be 150 cars long and stretch for about a mile and a half, which means that some towns with many grade crossings are effectively split in two by each train. According to BNSF studies, from 10,000 to 64,000 pounds of coal dust and chunks are blown and rattled off each mile-long train per 400 mile trip.

Two Northwest export terminal applications are in the study and permitting process. The export expansion plans and coal train hazards have created strong opposition from some Western leaders and citizens, and permits have been denied by state agencies for several proposed coal ports. Lawsuits have been filed against the EPA charging violations of the Clean Water Act from coal along the tracks. Twenty-one environmental groups asked in April 2013 for "an immediate moratorium on new coal leasing in the Powder River Basin" on payment, health and climate change grounds. In response, the Department of Interior said it already reports greenhouse gas effects from the burning of coal when considering new mines. It also noted ongoing reviews of leasing and pricing programs.

A new double pump-jack pulls oil from a well outside of Wright. In addition to coal, the ground under the Powder River Basin also holds reservoirs of petroleum and methane, lately exploited in a rush of wells and pipelines. The Basin now leads the state in oil production. The shale gas and oil is usually extracted by hydraulic fracturing – the injection of water, chemicals and fine sand into wells in the process called fracking – while coal bed methane is released by pumping water out of coal strata. Brackish wastewater from wells – called "produced water" – is pumped out on land, reinjected into wells, or pumped into filtering ponds. Wyoming has new regulations starting in March 2014 for energy operators to test fresh water wells and springs within a half mile of drilling sites to monitor any pollution.

The EPA estimates that each fracked oil well requires two to four million gallons of water. The water comes from aquifers used for drinking water and ranching. Water, already a contentious issue in the West, has become even more so as the gas drilling and coal mining intensifies.

Could this be the future? An integrated solar photo-voltaic and glass panel on the SW Wyoming Visitor Center near Cheyenne frames a set of mid-sized wind turbines on a hill outside the center. The center is a great advertisement for Wyoming's potential as a renewable energy leader. But Wyoming lags behind 14 other states in wind power, even though it has the eighth highest potential, according to U.S. Department of Energy figures. More large wind farms will soon be added in Wyoming’s south and central region.

The coal and petroleum-rich Powder River Basin also holds wind power promise. The Turners have had three test anemometers on their ranch for more than 6 years. "It's fantastic," Karen Turner said, looking at the wind speed and consistency record. "The capacity factor is 50 percent. Most wind farms are viable at 20 percent.” But lack of tax credit for renewable energy and other economic factors keep wind from being installed in their area, Turner said.

References and details may be found in the following:

http://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/research/energy/Coal/Default.aspx

http://www.eia.gov/energy_in_brief/article/role_coal_us.cfm

http://www.dailyclimate.org/tdc-newsroom/2012/04/coal-trains-montana

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

Photography and text Copyright © 2005 - 2017 (and before) Gary Braasch All rights reserved. Use of photographs in any manner without permission is prohibited by US copyright law. Photography is available for license to publications and other uses. Please contact requestinformation@worldviewofglobalwarming.org. View more of Gary Braasch's photography here.