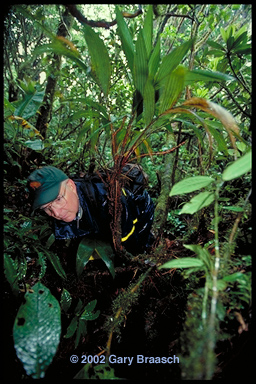

Pushing the Boundaries of Life: Tropics

For many years, it was thought that tropical rainforests

were essentially unaffected by climate change Now studies are showing

that not only were they changed during past events like ice ages, but

some areas are being affected right now by warming. At Monteverde Cloud

Forest Reserve, Costa Rica, clouds are forming higher, drying out some

of the habitat and causing changes in flora and fauna.

The most celebrated peer reviewed case is the disappearance

of the golden toads, Bufo periglenes. Each year Dr. Alan Pounds and others

search for the distinctive orange amphibian in its restricted habitat

along a narrow, fog-bound ridge. About 1500 toads were sighted in 1987.

But now the breeding pools remain empty -- the toad has not been seen

since 1991 and is feared extinct.

The golden toad and more than 60 other amphibians and lizards studied by Dr. Pounds are in decline apparently due to regional temperature increases lifting the level of clouds, changing the moisture regime and affecting a fungus that can be fatal to the animals. The species shown here, Atelopus varius, once common throughout Costa Rica, was not found at all in a recent survey, according to Dr. Pounds. The loss of the golden toad and other amphibians in Monteverde, Costa Rica, is particularly troubling because their habitats in the preserve are protected in the largely pristine montane rainforest. One cannot blame

habitat loss—a major cause of amphibian declines worldwide. A recent global survey of frogs and toads

showed that nearly all species listed as “possibly extinct” live in seemingly undisturbed habitats. Oregon State University herpetologist Andrew Blaustein notes that half of the amphibians that have been the object of recent studies

have been breeding earlier, a trend that correlates with evidence of global warming. Yet climate change,

he points out, is but one factor in species disappearing; disease, pesticides, and wetland destruction must

also be factored in. As for the loss of amphibians in Central America, Pounds suspected another culprit: an introduced

chythrid fungus, known to attack the skin of amphibians, that had somehow reached epidemic

proportions. In a paper published in January 2006, Pounds and colleagues hypothesized an

unpredictable synergy that climate can have with disease. Careful cross-analysis of temperature

moisture, and optimum growing conditions for the chythrid fungus indicated that a warming climate

favored the pest, allowing it to infect the skin of many frogs and kill them. This was especially true at

elevations from 3,300 to 7,900 feet (1000–2400 m), where night temperatures rose and, during the day,

warmer moist air increased cloudiness, protecting the fungus from hot sunlight. For more information on current amphibian research, see here.

Dryer conditions in the cloud forest concern Dr. Karen

Masters, who studies tiny Pleurothallic canopy orchids. Lenghtening dry

periods could drive some into extinction. "We are now seeing 2, 3

even 5 days in a row without moisture." she reports. "This is

very challenging to these orchids." Also, recent repeat surveys of

bats by Dr. Richard LaVal, and of birds by Debra DeRosier (repeating a

1979 survey by Dr. George Powell) shows lowland, dry habitat species are

already moving higher into former cloud forest areas.

Other big changes are being monitored in the tropics, too. Sixteen years of data on tree growth, tropical air temperatures and CO2 readings indicate that a warming climate may cause the tropical forests to give off more carbon dioxide than they take up. This wouldupset the common belief that tropical forests are always a sink for carbon, taking huge amounts out of the atmosphere.

The study, by Deborah and David Clark of the La Selva biological station in Costa Rica, and Charles Keeling and Stephen Piper of the Scripps Institution, reports that rainforest trees grow much more slowly in warmer nighttime

In other parts of the tropics, even in places that have been undisturbed for more than 4500 years, the rise in atmospheric CO2 appears to be changing the composition of the forest. In a paper in the 11 March 2004 issue of Nature, William Laurance and colleagues document that many tree genera in Amazonia are growing faster than they were in the 1980s.

Other tree types are declining in vitality. The study of 13,700 trees in 18 very isolated plots in Brazil concluded that increased carbon dioxide is the most plausible explanation for the abrupt shifts in species growth. This "could also have serious ecological repercussions for the diverse Amazonian biota" wrote the scientists.

"Sez who?": References 4 and References 7

Each of the foregoing photos reports on documented science, peer-reviewed published studies and scientific literature surveys. Those references are listed later in this Web site, along with climate change data, World View of Global Warming project advisors, and links to some sources of climate information.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

Photography and text Copyright © 2005 - 2017 (and before) Gary Braasch All rights reserved. Use of photographs in any manner without permission is prohibited by US copyright law. Photography is available for license to publications and other uses. Please contact requestinformation@worldviewofglobalwarming.org. View more of Gary Braasch's photography here.