Peru's great ecosystems -- mountains, rivers, rainforests and the people they support – are under great stress from rapid climate change.

A glacier has completely disappeared in the Peruvian Andes. Water for millions of people, agriculture and power is in shorter supply. Trees in the rainforest are migrating under stress from rising temperatures. From the craggy Andes mountains, the lush rainforests of the upper Amazon River and down to the desert Pacific coastline, Peru is experiencing active climate change. Average temperatures are up 1.8 degrees F (.75.C) since 1950, and in some regions it is rising faster.

As part of World View of Global Warming’s 15th year of witness to climate change, we returned in 2014 to some of the places Gary Braasch photographed at the beginning of his project in 1999, and reported on other impacts from global warming in Peru.

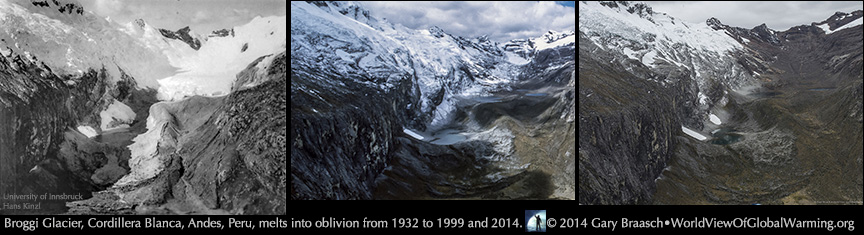

One of the most dramatic changes in Peru in recent years is the disappearance of Broggi Glacier in Huascaran National Park, a World Heritage site northeast of Lima. This is one of the first complete glacier losses to be photographically documented, with images from 1932, 1999 and 2014 showing how it had shrunk to a small icefield by the turn of the century and melted away totally in the few years since then. Gary Braasch had trekked up to 4600 m (almost 15,000 ft) in the upper Llanganuco Valley near Nevado Huascaran in 1999 to repeat a photograph made in 1932 by pioneering Austrian glaciologist Hans Kinzl. The Broggi was one of the glaciers that Kinzl and later Peruvian glaciologist Alcides Ames had studied and measured in coming to the conclusion that Andes ice was beginning to disappear rapidly. That glacier, which in the 1932 photo filled the upper valley (left image) and in Braasch’s 1999 image was a smaller glacier on the headwall, has melted away completely now– nothing there but the rocky cirque and a set of tiny tarns.

Many other glaciers in Peru, home to 70 percent of all tropical glaciers, are also shrinking, cutting off up to sixty percent of the water flowing into some rivers. Peru's people, irrigated farms and hydroelectric generation are heavily dependent on glacier runoff and the aquifers replenished by the melt water. The mountain range where the Broggi had been, the Cordillera Blanca, is the most glaciated region of the Andes, and is source of water not only for the desert Pacific coast north of Lima but also for part of the Peru’s Amazon Basin. Glacier area in the Cordillera Blanca is 25 percent smaller than in the 1930s, and losses are accelerating. The major river flowing west, the Rio Santa, prime water source in a desert landscape, is beginning to lose water (other glaciated Andes peaks, also losing glaciers, provide water to Lima and to communities across the Peruvian highlands).

Glacial water scientist Jeffrey McKenzie of McGill University said the decreasing water flow came as a surprise to local water managers. McKenzie, with Bryan Mark of Ohio State University and Michel Baraer also of McGill and others, was re-measuring water flow and quality in June 2014 as part of a long term study of glaciers and water use. “Most valleys are past peak water,” he said, and yearly average flow will only decrease. “Water managers thought it was coming in the future.”

But local farmers and villagers know. A survey in a farming valley below the mountains by Jeffrey Bury of UC Santa Cruz, found a quarter of the households did not have enough water for irrigation. They also reported that many perennial and intermittent springs were beginning to disappear. Water troubles are just beginning: The World Bank says that a third of Peru’s rural poor are without good drinking water, and that 70 percent of the nation’s power is hydroelectric.

To the east of the Andes lies Peru’s other very dramatic landscape, the upper Amazon, an area larger than France. The diverse rainforests of this basin hold one of the deepest reservoirs of sequestered carbon on our planet, according to a new Carnegie Institute study. This provides new value to forest protection and international negotiation over Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD), a prime topic at climate negotiations. Some of Peru’s tropical forest has been logged and is increasingly endangered by mining. At the same time, scientists say, these forests are being measurably affected by stress of disease and a very rapid rise in air temperatures.

Manu National Park east of Cusco in a rugged landscape of sharp ridges, cascading rivers and cloud and rain forest is a protected Biosphere Preserve and World Heritage Site. It may be the most biologically rich place on Earth. Although currently safe from logging and mining, Manu is not immune to the increasingly strong effects of rising temperatures.

In July we drove with forest ecologist Kenneth Feeley, of Florida International University, from Cusco east across the mostly treeless high-elevation Puna bunchgrass landscape to the sharp rim where the Puna drops away and the Manu jungle and the Amazon Basin begin. Below were the serrated green ridges of the Rio Kosnipata valley, where there are more species of trees on a single hectare than there are in all of North America. We know this because in this valley in 2003 ecologist Miles Silman of Wake Forest and colleagues, later joined by Ken Feeley, began establishing one hectare research plots rising up from lowland rainforest to cool windy cloudforest. In each of the 14 areas they worked with Peruvian scientists and students to identify each individual tree trunk and track its growth since the creation of the plots. They banded 14,000 trees, 1000 species in 250 genera.

The location of each plot was chosen not by ease of access or previous experience but to make an elevation gradient so that the next higher one is cooler; the air temperature naturally drops about 13 degrees C (23.5 F) from the bottom plot to the top one, an elevation change of about 2400 meters. And the ecosystem of the forest changes dramatically also, heat and humidity-loving tree types from the lowlands dropping out and cool-tolerant cloud forest species coming in as one moves up the plots. Trees common below are nowhere to be seen higher up. Each species of each genus has its preferred micro-climate. But climate is warming – and the trees are reacting.

Silman and Feeley’s resurveys (with eight colleagues) of these first 14 plots that spanned from 950-3400 m elevation show 85 percent of tree genera are moving upslope to cooler habitats. The average rate is 2.5 to 3.5 m per year (8 to 11 ft). The forest composition changes as some seeds are more successful upslope and by trees in good places growing faster, getting thicker, while old trees die out below.

So tree species can indeed migrate, which Silman knew from previous studies of Peruvian lake sediment cores in which can be read the slow transition and ecosystem changes from ice age to modern temperature. Temperature went up back then about a single degree per thousand years. Now, science projects a rise of more than 2 degrees C, maybe 4 – in less than 100 years. Seeing that speed increase was a “Wow” moment for Silman, and impetus for the series of plot studies. Trees in Manu are reacting, but Feeley and Silman calculate they’d have to more than double their upslope movement if they are to survive. The scientists continue their surveys, now in 22 plots that start at 750 m and extent to 3625 meters in elevation (about 2400 ft to 11,800 ft).

And where will the trees in the higher elevation plots migrate to? Temperate zone experience leads one to say that tree line – timberline – will rise. But here in Peru, the cloudforest hits a hard stop at the edge of the puna. Comparisons of old aerial photos show the edge of the forest has not budged in 50 years. The scientists are now studying a high forest plot at the 3425 meter edge of Manu and the bordering puna plateau itself to see what so far has kept trees from invading. Feeley also thinks that the trees at the lower range of each species life zone are dying faster due to changing climate before the species can move higher. Limits on migration speed, and migration itself and a static tree line “means the livable range gets smaller every year.”

Another rapid change is racing forward in Manu National Park, and a scientist finds himself in the middle of ongoing extinctions even while his field expeditions are finding new species. Alessandro Catenazzi of Southern Illinois University is a one of the world’s great tropical amphibian and reptile scientists. He recently discovered a previously unknown rainforest lizard and many new frogs, including what is thought to be the smallest frog in the Andes. A census and survey he collaborated on identifying 155 amphibian and 132 reptile species in Manu and its buffer zones, more than in any other protected area in the world.

But at the same time his collection trips at night for frogs are fraught with disappointment and loss -- species are being wiped out at a rapid pace by the deadly world-wide chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd). In his recent resurveys of 1999 data, Catenazzi has documented a 36 percent loss of species in the montane forest zone between 1200 and 3800 m. Losses to this fungus, which kills by thickening frog skin so the animal can no longer absorb water and exchange gases, are seen in lower regions of the park, too, but most of the complete disappearances of species have happened in the higher montane zone.

Catenazzi says the Bd fungus may not be as effective in the lowlands because of the warmer temperatures there. However, although apparently safer from fungus infection, the low elevation amphibians are much more liable to succumb to unusual warming which causes decreases in cloudiness and increases in the dry season.

The herpetologist collects amphibians nearly every night, ranging down into the rainforest to as low as 300 m, using his acute hearing as much as sight to locate the tiny creatures, like the Pristimantis species seen here. With a crew of volunteers and students, he measures each collected animal, including salamanders, and tests for the fungus on the skin. He is actively investigating frogs’ tolerance to temperature increases as well as susceptibility to the fungus, trying to sort out the conditions under which species are particularly vulnerable to both these deadly threats. Right now, the fungus is by far the worst plague on frog species, but temperatures are rising and lowland species are already experiencing heat just 3 to 5 degrees C below their thermal limit, Catenazzi has found. And he is not sure if species that survive disease will be able to migrate to cooler habitats.

"There is a bleak future,” said Catenazzi, "where amphibians that escape chytrid infection, because lowlands are too hot for the chytrid fungus, are ‘toasted' by high temperatures.” Ken Feeley told us, “We can argue the effects [of climate change] will be greater here. … We’re bound to see big changes – we’re already seeing them.”

For more on Peru’s shrinking glaciers, see http://www.worldviewofglobalwarming.org/pages/nvapril0814.php

Miles Silman’s lab: http://users.wfu.edu/silmanmr/labpage/

Ken Feeley’s lab: http://www2.fiu.edu/~kfeeley/

Work by both scientists in Manu is supported by grants from the National Science Foundation.

Alessandro Catenazzi’s page: https://sites.google.com/site/acatenazzi/

World View of Global Warming travel to Peru was supported by grants from a small environmental foundation and a cadre of individual contributors. Please add your support.

Images and information are available for publication and creation of stories for media.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

Photography and text Copyright © 2005 - 2017 (and before) Gary Braasch All rights reserved. Use of photographs in any manner without permission is prohibited by US copyright law. Photography is available for license to publications and other uses. Please contact requestinformation@worldviewofglobalwarming.org. View more of Gary Braasch's photography here.