Environment and Climate Change in Bhutan

“We commit ourselves to keep absorbing more carbon than we emit – and to maintain our country’s status as a net sink for GHG.”

The ‘Declaration of the Kingdom of Bhutan – the land of Gross National Happiness – to save our planet’ at Copenhagen COP-15

The fabled Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan stands alone among nations for its strong Buddhist faith, Constitutional concern for the happiness of its people, a monarchy that gave up power to establish democracy, its preservation of ecosystems and as the only nation to sequester much more carbon than it emits.

Bhutan’s history flows directly from powerful Buddhist monks and lamas who came into the region from Tibet beginning in the 7th C., including one who is recognized as the Second Buddha. Buddhist thought and practice deeply inform Bhutan’s civic and political life, revealed prominently in the humane and open-minded kings of the lineage first established in 1907. The first and second kings dealt with the British and then an independent India to maintain Bhutan’s sovereignty. The third king brought Bhutan out of isolation to join the United Nations, built the first hydroelectric dam, abolished serfdom, and established modern courts, national assembly and military. The forth king, who ascended to the throne at the age of 16 in 1972, advanced the concept of Gross National Happiness to measure Bhutan’s modernization and development in light of how they served the broader needs of the people. He also set into motion a new democratic constitution and gave up power to the national assembly and a council of ministers – eventually abdicating in 2006 in order to speed the establishment of constitutional monarchy. His son, the present and fifth king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, oversaw the open elections for the parliament in 2007 and 2008. The king is in the process of visiting every town and village in Bhutan, walking the streets and trails to meet citizens directly.

Bhutan’s understanding of and protection of its lands and ecosystems is another legacy of the fourth king, continued by the fifth. Although it shares the Himalayan landscape with Nepal and the mountain states of India, the differences among these countries are immediately apparent upon one’s arrival in Bhutan: It is more uniform in its architecture, Buddhist faith and people’s dress; vastly cleaner and less crowded with people and vehicles; and much more continuously forested. With a population of only 700,000 in an area about the size of Vermont and New Hampshire combined and almost no heavy industry, Bhutan has escaped the pollution and land degradation of other south Asian areas. Environmental protection is written into its constitution, which, for example, requires 60 percent of the land be forested. Bhutan has recently brought its philosophy and concerns to world attention at the Climate Summit for a Living Himalaya, fall 2011, and via a UN declaration of the human right to happiness in 2011.

In recent years, Bhutan, like other Himalayan areas, has seen an increase in landslides due to heavier rains, and some glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) as glaciers retreat. The GLOF threat is apparently Bhutan’s strongest climate change challenge so far. Bhutan’s 24 weather stations show a rise in temperature of about 1 degree C in summer and 2 degrees in winter since 2000. Recent studies show a reduction in irrigation water availability in some areas. Other global warming effects – shifting precipitation patterns, changing growing zones, more severe weather, worsening of air and water pollution and water scarcity -- are surely on the increase. So far Bhutan’s land protection and small population density are insulating it from the scale of damaging impacts on environmental and human health seen in neighboring countries.

Our visit to Bhutan in November 2012 was very short and confined to the central region. We are very grateful to our village hosts and contacts, guide, driver, tourist officials, NGO and agency leaders with whom we spoke. We traveled thanks to a grant from the Karuna Foundation – US to continue our documentation of climate change in the Himalaya and around the world and to provide information for the foundation’s planned support of climate adaptation in South Asia. We hope to return to work with Karuna projects and with environmental protection officials we met. Here are some of our first impressions of Bhutan’s significant progress in sustainable development with environmental protection accompanied by potential risks to its exquisite and rich ecosystems and cultural heritage.

Prayer wheel and painting of symbols of longevity outside of a main temple of the Trongsa Dzong, the largest of Bhutan’s monastery-fortresses. This kind of painting is common in Tibetan and Bhutanese art, found in public areas of many temples and public buildings. It depicts an ancient sage or god of longevity surrounded by symbols of the tree of longevity, springs and rivers springing forth from mountains, deer and cranes which are thought to live long lives. The symbology connects with Bhutan’s national vision of people living in harmony with nature and protecting species such as the crane.

Bhutan’s policy of Gross National Happiness seeks to balance material well being with the cultural and spiritual needs of individuals and society. The four pillars of Gross National Happiness are sustainable and equitable socio-economic development, conservation of environment, preservation and promotion of culture and the promotion of good governance.

The Northern Forest Complex, a portion of which extends up to Himalayan peaks Jhomolhari (7314 m) and Jichu Drake (6794 m), seen from the 3800m (12,300 ft) Chele La – the highest road pass in Bhutan. Below the ridge at lower left is the Kila nunnery. As is symbolized in the paintings of longevity and nature protection, the complex of three national parks north of Thimphu provide essential protection of complex ecosystems for the region.

Bhutan’s major rivers (called Chhu in Bhutanese) flow from and through the glaciated Himalaya, and not only feed the hydropower plants currently generating 40 percent of the national revenue, but also are subject to severe flooding as glaciers melt to create large unstable lakes. Bhutan has more percentage of its land covered in glaciers than it does in arable land. As summarized in a 2012 report by the Commission on Gross National Happiness, Bhutan is committed to a high level of environmental protection, but has “a significant risk of the localized impacts caused by global climate change.”

Ancient hemlocks, cypresses, pines and other trees cloak the Black Mountains east of Pele La. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan mandates the maintenance of “60 per cent forest cover for all times to come.” Because of this healthy forest, use of hydropower and lack of industry, Bhutan is one of the few countries in the world with net greenhouse gas sequestration, according to the United Nations. In addition, it has established more than half its area as parks, protected areas and biological corridors. Bhutan’s diversity includes more than 5,600 species of plants, nearly 700 species of birds and about 200 species of mammals. The latest reports say that one-third of the of the country's GDP is derived from renewable natural resources – wood, livestock and farm products - which employ 64 percent of the population.

Black-necked cranes (Grus nigricollis) are among the charismatic threatened and endangered species within Bhutan, along with the tiger, red panda, snow leopard, rufous-necked hornbill, rhino, langurs, and many others. International attention on loss of habitat for the migratory cranes lead to administrative protection of a primary wintering area in the Phobjikha Valley of central Bhutan, where more than 300 of the large birds with a 7-8 foot wingspan feed on dwarf bamboo and other plants from October to February.

Phobjikha Conservation Area protects about 60 square miles of the valley which is leased by the government to the Royal Society for the Protection of Nature (RSPN) for the purpose of conservation management. The cranes are also protected from hunting everywhere in Bhutan. Expansion of grazing and farming areas and draining of the wetland habitat are the prime threats to the birds. The RSPN works with farmers to keep strict limits on agricultural use and human traffic through the valley when the cranes are present. Six cranes have been radio tracked since 2006, to help monitor their migration, mating and lifespan.

At dawn in November, a rich layer of frost coats the upper valley at an elevation of 3000 m. This area of the valley, which is a broad glacial-carved bowl extending from the Black Mountains to the Punatsang Chhu, is center of an integrated conservation and development Program set up by the RSPN to balance the needs of the human community with the cranes and other parts of the ecosystem. RSPN Crane Center assistant director Tshering Choki commented that climate warming is being reported by local residents, including warmer evenings in the winter, seeing less snow on the hills and valley floor and increasing rainfall and erosion. .

Tiny communities of 30 or fewer families ring the Phobjikha Valley, built with the typical three–story Bhutanese farmhouses. Most of the fields are planted with potatoes, a prime export crop. Families typically own less than three acres of farmland, but about 40 percent of households own up to 10 acres, according to the 2011 Gross National Happiness Commission report. Community forests, typically around 100 Ha (250 acres) in size, cloak most of the upper slopes and are used by the individual villages mostly for fodder and firewood. The presence of the cranes provided another reason for protection and conservation – ecotourism, which is now a major source of income in the winter. A November Crane Festival, birding, and trekking routes are the main attractions.

Farm and road along the Lekchi stream, a tributary valley of Phobikha. Agriculture is the main source of livelihood in Bhutan, according to government reports. Even though it contributes less than 10 percent of national income, agriculture provides more than 78 percent of monetary income in rural households. Almost 70 per cent of Bhutanese are engaged in subsistence agriculture, but less than eight percent of the land is suitable for farming.

Women at a farm and guest house in Phobjikha Valley feed cows with kitchen scraps. Creating less waste and reducing the needs for fodder from the forest are part of the common environmental awareness of many Bhutanese. Tshering Choki of the RSPN said that organic agriculture is gaining but still much pesticide and agricultural chemicals are used on potatoes, rather than compost. This is one of the challenges ahead in Bhutan’s announced goal of become a fully organic nation. “When we do our [environmental] awareness training,” said Tshering, “we tell people that if you only do one crop you will introduce weed species and reduce nutrients of the soil. Some people do realize that certain weed species could be brought by using herbicides and pesticides.”

Tshering Phuntsho, Coordinator of the Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods Program of the Royal Society for the Protection of Nature, said the Society’s program to install solar panels on every house in the valley was “one of the most successful programs we had.” Previously a plan for solar hot water heating was not very successful, but families were eager to get solar pv electricity panels because power from the national grid had not reached the valley yet. The program provided low interest loans to the families to buy and install the panels. In an ironic and undercutting development not long after, the governments of Bhutan and Austria collaborated on installing grid power to Phobjikha valley. Trenching the powerlines underground so the wires would not to be a danger to the cranes was completed in 2012. Tshering said that although most houses are now connected to national power, the solar panels from the RSPN program were still in use because solar power is cheaper than that from the government.

In the dark ground floor of her ten year old family home, Sangay Lhamo, 26, sorts seed potatoes put aside for next year after the harvest on the family’s less-than-one-acre fields. Potatoes are the primary export crop of Bhutan, almost all of it going by truck to India, and about 28 percent of the national crop is grown in the Phobjikha Valley. Acccording to the local leaders of the Royal Society for the Protection of Nature, with government encouragement over the past 40 years the valley and other farming areas have become very dependent on potatoes. For many decades previously the villagers of Phobjkha had been migratory, moving seasonally down to the larger river valley near Wangdue Phodrang in winter and up to the Phobjikha Valley in warmer weather. They grew a diverse mix of crops which were part of a bartering economy rather than being in the export market, so farming income was low. Now there is nearly a monoculture of potatoes – 93 percent of income is from potatoes and 95 percent of the fields are used to grow them – and the valley is more prosperous. RSPN leaders there said the valley may have the largest number of power tillers and tractors in Bhutan (whereas most farmers use bullocks to power fieldwork).

The success of potato growing has been a “major influence “ on increasing population in the valley and reduction in seasonal migration. It also meant that more people were in the valley through the winter, thus putting pressure on crane wintering habitat. In addition to added management issues over the wildlife, worries are rising that the valley and its potato crop is now more subject to market fluctuations, climate change and disease and pest outbreaks. Tshering Phuntsho of RSPN said that a recent study of climate vulnerability (to be published by the RSPN in 2014) found that “the people are more vulnerable here in Phobjikha because of their dependence on a single crop.”

First grade schoolboys returning home from school, crossing over part of Lekchi Chhu in a valley adjoining the Phobjikha. This and a larger old span in background are the only crossings between the two villages of Ramachen, which has the school, and Tanche on this side. During severe rainstorms, which are becoming more common, the river rises and it is difficult for kids to cross back and forth to school. It also becomes impossible for trucks to navigate the road carrying potatoes and other crops like carrots, turnips and cabbage to market. Thus a new bridge will be built here in a program by the UN Clean Development Fund Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility (LoCAL), as one way to adapt to expected increases in storm downpours. LoCAL initially is targeting two village groups in the Phobjikha valley.

Forest preservation is a central tenet in Bhutan’s philosophy and land management, exemplified by Black Mountain National Park – now incorporating part of the Phobjikha Valley and called Jigme Singye Wangchuk National Park after the fourth king. Because it is about 70 percent forested and has such low industrial and vehicle emissions (an insignificant 2040 Gg of CO2 in 2008), Bhutan is a net sink of greenhouse gases. But emissions are rising and a 2011 report said that per capita carbon emissions almost tripled between 1990 and 2000.

Overlooking Chendebji village between Pele La and Trongsa. The village and surrounding area with 95 households is powered by micro-hydro generation, piping water from the upper valley to a small powerhouse at the lower left. The project was the first such project under the UN’s Kyoto Protocol Clean Development Mechanism. Seen more broadly from the viewpoint of the Bhutan Gross National Happiness Commission, this local electrification project and similar local programs have resulted in “poverty reduction, expanded educational enrollments, impressive declines in child and maternal mortality and securing high access levels in the provisioning of water and sanitation facilities.” However, one in four Bhutanese still remains in income poverty. And although child and mother mortality rates are decreasing, chronic malnutrition affects one third of Bhutanese children.

The report of the Gross National Happiness Commission said that where human development standards were higher in Bhutan the impacts of climate change would likely be felt less, but the poor would be much more affected. Other factors disadvantaging the poor and more remote settlements in Bhutan were said to be distance from centers of economic activity, schools or hospitals; limited local governance capacity and less awareness of climate risks. The report warned that “Bhutan’s gains remain fragile and at risk of reversal.”

The area around Chendebji village makes most of its farming income from potatoes and grazing animals, as well as gathering a folk medicine fungus from the forest to sell. Residents harvest vegetables and barley for subsistence, as this woman is doing by the ancient method of drawing the grain stems between two bamboo sticks.

Many farmers in Bhutan also compost with food scraps and greens and forest fodder and mix leaves with animal waste to create natural fertilizers. The Bhutanese Tarayana Foundation reported that there are changes taking place as farmers react to climate changes through seed selection and crop timing. A recent survey of farmers near Punakha found 91 percent of them found it harder to access enough water for paddy irrigation over the last two decades, because of decreasing and delayed monsoon rains. This change was confirmed by records from 1990 and 2010 at six meteorological stations in the same district.

But unlike some areas in adjoining India and Nepal, climate shifts so far may be more gentle or moderated in Bhutan. One survey found that 19 per cent of farmers questioned noticed changes in cropping pattern, while 63 per cent did not observe any change and the remaining 19 per cent were uncertain of the change. The Gross National Happiness report said some farmers are shifting to earlier rice planting, which has effects on when they can plants other crops and on water allocation. Other farmers at villages higher into the mountains, according to a WWF study, report that temperature has risen in the last 15 years and that it is generally a good thing: Higher elevation farms can now grow chilies, cabbage, cauliflower, beets and eggplants.

Woman in Chendebji , Bhutan, draws water from a spring faucet that serves three households. Residents here credit the government with bringing clean spring water and electricity without changing the beauty and solitude of the community nor the patterns of land use and architecture. Thinley Namgyel, Chief of the Climate Change Division of the National Environment Commission said that there are water scarcity issues seasonally in Bhutan, but no water purity problems. Farmers can adapt to changes in climate, like temperature changes, he said, but there are also more immediate threatening events like severe flashfloods and landslides following severe rains.

Bhutan’s government science leaders are well aware that climate is going to change more and that the nation must be ready. The Secretary of the National Environment Commission, Ugyen Tshewang, is a geneticist who helped set up Bhutan’s own seed bank to protect the genes of important crops like rice, beans and corn. He said Bhutan has 60 varieties of corn, 58 of beans, and more than 300 of rice. Among them is an upland rice which does not need paddies filled with water. Among Bhutan’s needs, Tshewang said, are “good scientists” to work more on characterizing and adaptation of food crops.

The small concrete headworks dam on Cheba Chhu for the micro hydro system in Chendebji. It is being inspected by the caretaker and bill collector for the system, Nimashi, who is also a carpenter and house builder. The water is piped 850 m down the valley to a generator which creates about 70 KW of power to serve 95 households with less than 500 people. The system was completed in 2005 with funding from seven developed nations in a consortium called E7, sanctioned by the UN Kyoto Protocol. The electricity going to homes, shops and the village school and temple replaced wood and kerosene for light and some heating, and makes possible the use of electric stoves, TV, electric saws, rice cookers and other appliances. Under the rules of the Clean Development Mechanism of the Protocol, the hydro project creates a carbon credit of 500 ton C per year for the consortium nations, over an expected 21 year lifespan. According to Nimashi, the average household pays about 1650 Bhutanese Nu per year for electricity (about U$33), and businesses twice that.

In this kitchen in Chendebji – a temporary room while the family’s new home is being built - a woman cooks with bottled gas burners, wood in the stove, and an electric rice cooker. This mix is common in Bhutan, with each of the three energy sources contributing about a third of domestic cooking energy. But despite the electrification from micro hydro and much larger dams powering the national grid, wood is still the primary heating fuel for households and businesses, and accounts for more than 90 percent of national energy consumption. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization says Bhutan has the highest per capita use of fuelwood in the world.

Rukubji is a very old village built on a ridge between three rivers on the edge of the Black Mountains. Some of the homes are more than 200 years old, with eroded mud and bamboo walls. The ridge on which the village is built is said to resemble a snake, a harmful spirit, which in the area’s ancient history and mythology was subdued by the founder of Bhutanese Buddhism, Guru Rimpoche. This and three nearby villages totaling 90 households are known today as being part of another successful micro hydro installation.

The compact grouping of the homes in Rukubji is said to be unusual for Bhutan but the home design is not. Narrow stone pathways pass between three story walls and pocket gardens divided by woven bamboo fences. Drinking water is piped from springs to each house, and the village has outdoor toilets between some of the homes. The town has had electricity since Japan paid for the micro hydro system 20 years ago. Households use the power for lights, rice cooker, water kettle, stove, TV and heat, but in most homes wood is still the primary heating fuel. Humboldt State University of California recently installed “GridShare” devices to manage the flow of power and reduce brownouts. Some electricity also comes into town from the national grid whose power lines soar overhead across the valley.

Three young teenagers, Pemba Wangchuk, Phub Tshering and Pem Tshering, far from wanting to flee the village as young men often do, vowed they wanted to stay in Rukubji, finish school and become monks. Bhutan is a youthful nation, with more than half the population being under 25 years of age. Youth 15-29 make up more than a third of the labor force, but they are also the least employed, with an unemployment rate in 2012 of 7.3 percent. Since Bhutan has an enviable national unemployment rate of just over 2 percent, according to Labour Force Survey reports, there is a serious issue in youth unemployment In recent years the rate of youth without jobs has been as high as 9 percent, with most of the problem centered in the cities. News reports and blogs have blamed some of this on a mismatch between training and work needs, and some on an unwillingness of youth to take working-class and laborer jobs.

Bhutan has four major river basins, some of which rise in Tibet and flow through the mountains on the northern boundary of Bhutan. They create the landscape and inhabited valleys as they flow south, eventually to cross into India and empty into the Brahmaputra River. Recently they have been seen increasingly as the major engine of Bhutan's economic growth as sources of hydropower. Here the Punatsang Chhu (River) flows near Wangdue Phodrang and Punakha. The river’s forests, wetlands and gravel bars are habitat for one of the most endangered birds in the world, the white-bellied heron (Ardea insignis) (a close relative of the great blue heron of North America). This bird is Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List with fewer than 250 mature individuals in a scattered range from Myamar (Burma) to India. The Royal Society for the Protection of Nature (RSPN) began a conservation program and the government of Bhutan has recognized the riverbed area of Punakha-Wangdue as important to about 30 white-bellied herons, designating some of it as a protected habitat to preserve the species.

Just seven kilometers downstream from Wangdue Phodrang, the Punatsang Chhu’s landscape and agricultural terraces are torn apart by the construction of Bhutan’s newest major dam project. In an estimated total one billion dollar project funded through grants and loans from India, Bhutan is building two large hydroelectric projects that will block and divert the Punatsang Chhu. Eighty-five percent of the electricity will be exported to India. Construction, engineering and most of the labor is being contracted to the Indian Larsen & Toubro company. The uppermost dam seen under construction here will not have a large reservoir but reportedly may back up water into some of the areas considered prime white bellied heron habitat.

The Punatsangchhu I Dam construction site in November 2012 was being prepared to span the riverbed with rebar and concrete to make the 137 m high and 279 m wide dam. The river now flows through a diversion tunnel to allow construction at bedrock, but when the dam is complete the four intake tunnels at mid left will suck the backed up water down 9 km to an underground power house housing six turbine units with a total generation capacity of 1200 MW. A second phase of the project will create even more electrical power. Bhutan now has 5 large dams operating and a number of small hydro projects for a total capacity of about 1500 MW, and more than 70 percent of that is exported to India, generating about half Bhutan’s income.

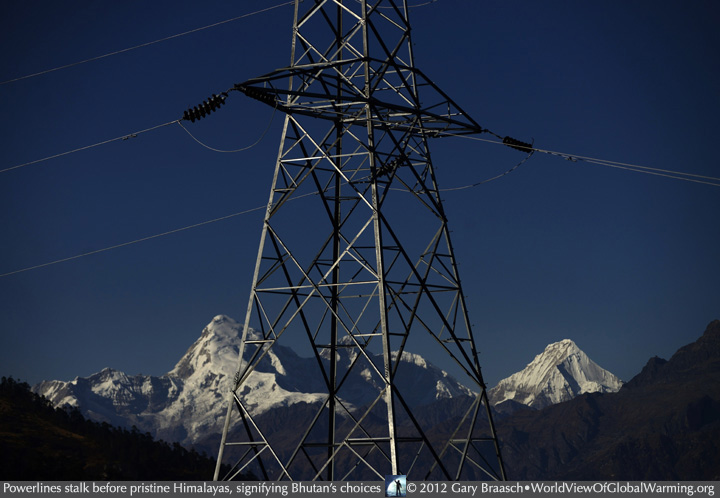

Bhutan plans to be a major exporter of hydropower in order to become self-sufficient in income and foster the development of its people. The dams on the Punatsang Chhu are the first of a series of 10 hydropower projects which will be built in Bhutan with Indian financing for a total installed capacity of 11,576 MW by 2020 -- giving another meaning to the painted centerline marker, “Dam Axis,” at the construction site. The scale of the plan to dam so many rivers has raised questions ranging from the dominance of India in financing and construction to the loss of glaciers and changes in rainfall forseen for the Himalayas.

At the Climate Summit for the Himalayas, which Bhutan hosted in Thimphu in November 2011, the threat of climate warming to hydropower was spelled out, including increasing risk of Glacial Lake Outburst Flooding (GLOF); variability of runoff and siltation from glacier melting and monsoon changes; and loss of reservoir water due to increased evaporation.

Conservation groups and ecologists have raised many questions, including the threat to crucial river ecosystems directly and by diversions. Even a dam with little reservoir but a diversion of the water into turbines (called “run of river” hydropower) greatly disturbs the riverbed downstream. Karma Chophel of the National Environment Commission was quoted in news reports saying, “building the hydropower projects will disturb the free flow of rivers,” and damage rare aquatic systems which are little studied but known to be rich in species. A WWF vulnerability assessment of Wangchuck Centennial Park states that dams block all connectivity for the flow of nature up and down the rivers. WWF also said reservoirs and diversions may raise water temperatures even more than climate change, affecting even more plants and animals.

The kids at this road worker camp near Paro may look happy, reacting to a foreigner pointing a camera at them, but a glance at the shacks behind them, compared to the homes of most Bhutanese, gives one indication of the plight of the imported labor force that Bhutan relies on. According to a report from Reuters in 2012, there are an estimated 60,000 laborers in Bhutan, Indian and Nepali mostly, doing the rough work of digging out landslides and constructing roads. Indian laborers and construction workers are also employed at the dam projects contracted by Indian companies. Although the minimum wage in Bhutan is 350 Nu/day (about $7), migrant workers from India and Nepal may get only 200 Nu ($4), according to people we spoke with in Thimphu. Indian and Nepali workers have been employed in Bhutan for many years, and the legal and cultural status of them and their families has been the cause of tension, conflict and even some bloodshed in southern Bhutan. The government began in the late 1980s to require northern Bhutanese dress and language, to control immigration and determine citizenship based on national origin. Life became intolerable for many "amid ethnic tensions" in the words of the UN High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR), and more than 100,000 people were deported or left Bhutan. Most settled in refugee camps in Nepal, and since then under programs of the UNHCR more than half have been resettled in other countries -- 35,000 of them in the United States.

View above from Pele La, a highway pass between Punakha and Trongsa.

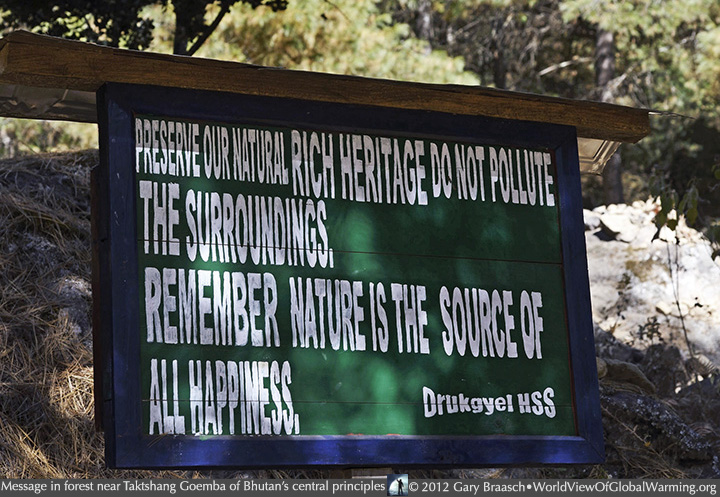

This sign speaks for itself, as does the view above from Pele La, a highway pass between Punakha and Trongsa.

Monks and students at the Chimi Lhakhang temple near Punakha plant trees, symbolizing all that Bhutan believes in culturally and actively doing what is necessary to get ready for the changes of a warming climate. Recent reports, including those prepared for the regional climate conference in Bhutan in November 2011, are clear and detailed about what’s in store for the people of Bhutan – and all in the Himalaya region:

• Landscape changes like GLOFs and landslides.

• Food insecurity.

• Increased disease, including malaria in the southern lowlands of Bhutan.

• Livelihood stresses and destruction.

• Water scarcity, in agriculture, community supply and hydropower generation.

• Population migration and cultural conflicts.

Peaks vs Power: Will Bhutan be able to protect its environment, ecosystems and magnificent landscape while generating income and allowing its people to develop within their culture? Uniquely among nations, it has this choice and a chance also to be a model for a world searching for answers as dangerous climate change looms.

Whether it has already stepped over the edge and will damage its rivers irrevocably with its hydropower plan is a big question. As its ministers and other attendees at the Climate Summit for the Himalaya were reminded, climate change adaptation is mainly about water: “Water resources and how they are managed impact almost all aspects of society and the economy, in particular health, food production and security, domestic water supply and sanitation, energy, industry, and the functioning of ecosystems.” Environmentalists quoted in the Kuensel newspaper in Thimphu warn that Bhutan is “making a water bomb” by overdeveloping hydropower without enough environmental assessment. Ugyen Tshewang, leader of The National Environment Commission, told us, “Water is our lifeline. We have good resources but they are diminishing…. Dry seasons, droughts, are worse now, everywhere in the country.” “Without the environment,” Tshewang said, “there is no hydropower.”

Detail of 50 meter figure of the Buddha in Bhutan showing the "mudra," (gesture) toward the Earth with his right hand. This position is also known as "Earth Witness," and represents him calling the Earth to witness at the moment of his enlightenment. In one way this symbolizes the actions of Bhutan from its religious heritage to its Constitution and attitudes of its people as a model to the world of an ecological nation.

Please see other Himalaya stories in the Climate Changes menu above.

OR

Water | Landslide | Cookstoves | Ganges Glaciers | Bhutan

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

Photography and text Copyright © 2005 - 2017 (and before) Gary Braasch All rights reserved. Use of photographs in any manner without permission is prohibited by US copyright law. Photography is available for license to publications and other uses. Please contact requestinformation@worldviewofglobalwarming.org. View more of Gary Braasch's photography here.